Here’s a stumper that many would’ve encountered while working through a deal: “In an M&A, which type of deal consideration is earnings-accretive: cash or stock?”. In this post, I’ll try to answer this question and also shed some light on how accretive deals can still be value destructive.

What is earnings accretion?

Before we delve into this topic, some primer to the reader - earnings accretion refers to a higher post-transaction earnings per share (EPS) for the acquirer compared to the standalone EPS before the acquisition.

The true answer to the question cannot be conclusively found without some additional information. Think about it. The test of value creation from M&A is in essence a cost-benefit analysis. Concluding whether a deal is accretive or dilutive by solely looking at post-merger EPS ignores a comprehensive account of the costs of funds used in the deal. Moreover, since companies aren’t required to amortize goodwill, the EPS accretion test is based on inflated earnings to begin with.

An inaccurate test

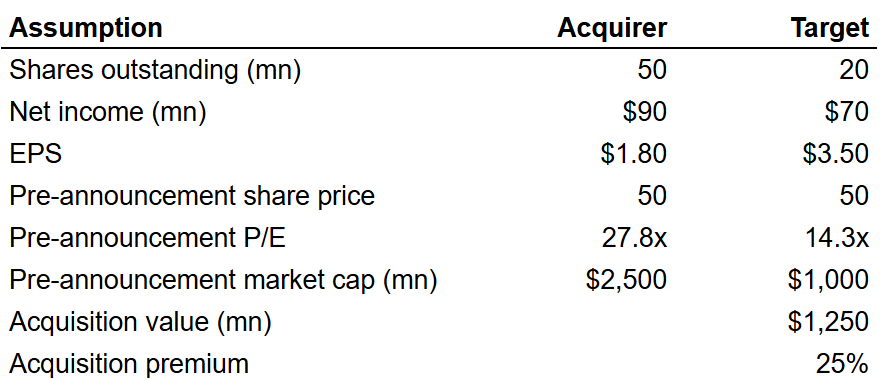

To understand why the accretion test fails to capture the true cost of acquisition, consider the following simplified example: Company A (the acquirer) has screened a potential target, a zero-debt firm with a market cap of $1.00bn. The buyer is willing to pay an acquisition premium of 25%, resulting in an offer consideration of $1.25bn that can be paid in cash or stock.

A cash offer would help avoid the equity dilution but increase the interest expense (assuming the cash required is financed at 6% pre-tax). The deal assumes no revenue or cost synergies (in many real-life deals, companies are bullish about their synergy estimates to justify the EPS accretion and the hefty premium paid). Hence, the acquisition is clearly value destructive since the target is purchased at a $0.25bn premium despite lack of synergies. Nevertheless, the deal is accretive to earnings (see tables below for calculation) because the target’s net income more than offsets the after-tax interest expense from new debt used in the acquisition.

The table below presents an alternative all-stock scenario that results in issuance of about 25mn in acquirer’s stock to fund the deal. The EPS accretion in this scenario is higher (at $0.33) than that in an all-cash deal, which is counter-intuitive at first sight. The higher accretion is caused by significant difference in valuation - acquirer’s equity trades at ~28.0x earnings compared to the target’s significantly lower ~14.0x. In summary, a deal will be EPS-accretive (even if it is value-destructive) provided that the acquirer’s P/E is greater than the target’s.

An alternative framework

It is a common misconception that all-cash deals that don’t risk equity dilution are safer than all-stock or mixed-consideration deals. Debt-fueled acquisitions impose significant risk on future shareholder returns. The traditional EPS accretion/dilution test does a poor job of capturing the full economic cost of acquisitions particularly in all-stock or mixed consideration deals because, unlike cost of debt, the cost of equity is not explicitly accounted for on the income statement.

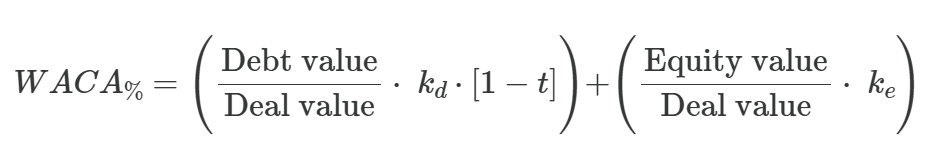

A better alternative to the EPS accretion test involves computing the weighted average cost of acquisition (WACA) for a deal. WACA is a slightly different version of the popular weighted average cost of capital (WACC), purpose-built for the specific sources and the respective cost of funding for a deal:

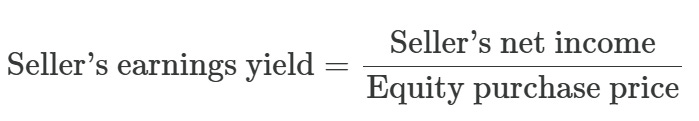

kd and ke in the function above refer to cost of debt and cost of equity, respectively. An acquisition is accretive if the WACA is greater than the target’s earnings yield measured as:

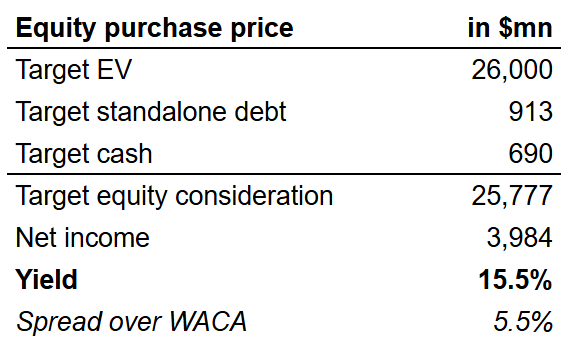

Diamondback Energy, Inc. (NASDAQ: FANG) recently concluded the acquisition of a private peer, Endeavor Energy Resources, L.P. in a cash and stock deal, an apt example to assess WACA. Endeavor’s EV was valued at about $26.00bn, of which $8.20bn was paid in cash while the remainder was paid through issuance of 117,267,069 FANG shares. Other pertinent information about the deal is shown below:

We rely on the definitive proxy filing for Endeavor’s financials such as FY23 debt and cash, which are necessary to calculate the implied equity purchase price of $25.78bn. Endeavor’s net income and the cost of debt is also based on disclosures from the proxy filing. FANG’s cost of equity is estimated as the inverse of its forward P/E ratio as of the trading day before the deal was announced (FANG was trading at 8.35x NTM EPS on 9-Feb-24).

Using these inputs, it can be seen that FANG acquired Endeavor with a significant spread over WACA - Endeavor’s earnings yield of 15.5% is much higher than the 10.0% in cost of funds utilized to purchase Endeavor. FANG hasn’t quantified EPS accretion for the deal but expects ~10% free cash flow per share accretion in 2025.

In conclusion…

The M&A landscape has undergone a sea of changes over the past few years. The dealmaking furor witnessed in 2021 has withered away since. Still, inorganic growth is an integral part of a healthy corporate strategy. A change in the US government and its policy stance signals that de-regulation is likely to drive further dealmaking. Companies will continue to obsess over accretiveness to justify the deal.

Despite the drawbacks, accretion test remains the most efficient quick and dirty ex-ante method to assess a deal and are here to stay. However, equity owners can always ascertain the long-run value creation from a deal simply by measuring the total shareholder return, although not its entirety can be attributed to a good acquisition.